Epilepsy. The Swahili word is kifaafaa, origins possibly from the verb “kufaa” meaning “to die”. Although overshadowed by diseases such as AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria, most of the same diseases and conditions present in the United States are also present in East Africa.

My interest in epilepsy in Tanzania was sparked over a pot of chocolate fondue in Arusha town. I had met with my election buddy, founder of “Mwangaza” (www.mwangaza.com) who is working on an epilepsy initiative that will tackle multiple facets of the epilepsy problem within Tanzania over a 2 year time span.

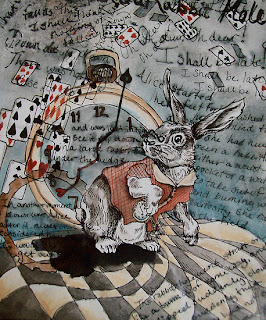

Although the exact prevalence of epilepsy is unknown in Tanzania, it is estimated to be higher than that of western countries, ranging from 5 to 75 cases per 1000 patients (Foresgren, Winkler). There are many theories, including increased incidences of diseases such as neurocystocercosis, cerebral malaria, and meningitis, head trauma, or toxins. While there is a growing body of evidence regarding prevalence of epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa, we have not even begun to go down the rabbit hole.

Cerebral Malaria

Of the four species of plasmodium known to cause malaria, Plasmodium falciparum causes the most severe illness. Although many cases will remain as simple malaria, complicated malaria can cause acute renal failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome, changes in blood homeostatis, and cerebral malaria. Cerebral malaria carries a drastically increased risk of mortality and is often characterized by seizures.

As diseased erythrocytes flow through the vasculature of the brain, they begin to stick to the endothelium and disrupt blood flow. Cytokines are released to fight the disease, but, also do harm to the brain tissue. Despite treatment, neurological damage may persist. It is hypothesized that CNS infections, such as cerebral malaria and meningitis, may play a role in epileptigenesis for some patients living with epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa.

While many questions remain to be answered, undoubtably many patients would benefit from rapid malaria treatment to reduce the risk of progression to complicated malaria.

Neurocysticerosis

Pigs are filthy animals. Cysticercosis results from infection by Taenia solium, a parasitic worm that is acquired from undercooked pig meat. Infection with the adult worm causes taeniosis, tapeworm infection. The worm grows and begins to shed eggs which are released into the host’s feces.

The eggs can then be potentially ingested by other pigs, other humans, or auto-infect the original host. These hatched worms will never leave the larval stage, but are deposited into the host’s tissue where they develop into cysts capable of causing an immune response. Inflammation from the host’s immune system attacking the parasite results in the clinical symptoms of cysticercosis. Eventually the legion will calcify and the inflammation will disappear.

Neurocysticercosis results when the parasite has penetrated the blood brain barrier and forms lesions in the brain tissue. It is possible that the lesions will be asymptomatic, but there is a growing body of evidence to support high incidences of epilepsy or recurrent seizures in patients with neurocysticercosis (NCC), especially during the phase of intense inflammation.

Without access to neuroimaging technology, it is important for physicians in areas of endemic NCC to be able to identify symptoms. Cysticercosis can be treated with anti-parasitic medication, such as albendazole and praziquantel, and steroids. Additionally, anti-epileptic medications are helpful in symptomatically managing the disease.

Neurocysticercosis is the leading cause of adult onset epilepsy in the world, and it is completely preventable. Increased education on proper hand-washing techniques and the dangers of ingesting undercooked pig meat could significantly reduce the prevalence of seizures and epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa.

The majority of patients living with epilepsy in sub-Saharan Africa are untreated. WHO estimates that over 80% of patients with epilepsy in Africa do not receive any treatment. Untreated epilepsy leads to progressive brain damage, and patients are at risk of physical harm when they seize. Major obstacles to successfully manage patients with epilepsy include a lack of resources, lack of experience in treating epilepsy among health care professionals, a lack of understanding of the disease for patients living with epilepsy, and cultural barriers.

Resources

A simple lack of resource is the most obvious reason for the treatment gap. The only medications I was aware of that were being used to treat epilepsy in Tanzania are phenobarbital, phenytoin, and carbamazepine. Valproic acid seems to also be a common treatment in third world countries.

In Tanzania, phenobarbital is the most frequently used medication. It is far from being first line treatment of epilepsy in the United States for the simple reason that many patients taking it turn into a sort of zombie. It is very difficult, if not impossible, to be high functioning while taking large daily doses of phenobarb to control seizures. However, it is very effective in controlling seizures and patients can safely take it without needing blood draws.

There is a shortage of neurologists in Tanzania, and with this, there is less understanding in how to effectively manage the disease and manage the medications. Many health care facilities may not have labs with the capacity to monitor serum levels of carbamazepine or phenytoin, essential to avoid blood dyscrasias and seizures that can result from high phenytoin levels. Additionally, many patients with epilepsy live in very rural areas, where seeking any kind of medical care is a challenge let alone getting to a larger facility with the capacity to determine serum drug levels.

Carbamazepine is available in Tanzania, but it is only available in larger urban areas. A challenge for my friend, that is developing the epilepsy initiative, is not only to find patients and get them started on an antiepileptic medication, but also to keep them on that medication. As she goes out into the villages, she not only has to provide medication on this visit, but ensure that systems are in place for the patient to continue their therapy. The wider availability of phenobarbital again makes it a more desirable choice for this reason.

Culture

Epilepsy is known as “kifaafaa” in Swahili, which may be translated as “deathdeath”. The disease is not understood well by the majority of the population and is surrounded by a number of superstitions. Learning about these was one of the most interesting aspects of the disease; to treat the epileptics of East Africa, these beliefs must also be confronted.

Many people believe that epileptics have been cursed or that they are being possessed. Under this belief, a person that is seizing is less likely to be helped, even if they fall into the cooking fire. Many people that have been living with epilepsy for a long time have been badly burned. Poorly controlled epilepsy also results in decreased brain function, as a result from a lack of oxygen delivered to the brain during seizures. Epileptics are the victims of social stigma, increased physical risk, and risk of neurological damage.

Another friend of mine was working to set up a homeless shelter for women in Usa River Village. He wandered the streets with Ibra, a former student, as an interpreter and met women in the worst situations of life and listened to their stories. One woman who was of great interest to me, was covered in burns. She told him she had a “fainting problem”. She also exhibited neurological damage; she was not really all there. Her strangeness drew neighbors out of their homes, who in turn laughed at her. She had virtually no support system, and neither she nor her neighbors understood that her condition could be treated with medication.

Given these stories, my heart goes out to Mwangaza. I have only begun to go down the rabbit hole, but Mwangaza is already in action, setting out to tackle a disease state that is not only misunderstood by the general population, but also has little scientific research behind the prevalence, origins, and treatment in this geographical area. If given the opportunity to go back and make myself useful to Mwangaza’s initiative, I would do so in heartbeat.

References:

Winkler AS et al. Prevalence, incidence, and clinical characteristics of epilepsy- a community based door-to-door study in northern Tanzania. Epilepsia 2009; 50(10):2310-2313.

Mbuba CK et al. The epilepsy treatment gap in developing countries: a systematic review of the magnitude, causes, and intervention strategies. Epilepsia 2008; 49(9):1491-1503.

Ngoungou EB et al. Cerebral malaria and epilepsy. Epilepsia 2008; 49(Suppl. 6): 29-24.

Zafar MJ. Neurocysticercosis. eMedicine Medscape 2009. Taken from http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1168656-overview on 1 November 2010.

Winkler AS et al. Epilepsy and neurocysticercosis in sub-Saharan Africa. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2009; 121(Suppl. 3): 3-12.

Quet F et al. Meta-analysis of the association between cysticercosis and epilepsy in Africa. Epilepsia 2010; 51(5):830-837.

just dropped into your blog - writing on a thesis on epilepsy in Tanzania myself. intense pics - just like the condition. are you involved or merely posting collected stories?

ReplyDeletecheers

toni